Florence Kling Harding was a few steps ahead of the women of her time. Thanks to passage of the 19th Amendment allowing women to vote for president, Mrs. Harding proudly cast her first ballot in November 1920 – for her own husband.

Florence Kling Harding was a few steps ahead of the women of her time. Thanks to passage of the 19th Amendment allowing women to vote for president, Mrs. Harding proudly cast her first ballot in November 1920 – for her own husband.

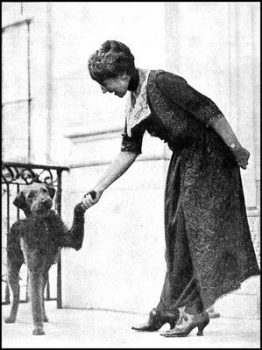

Born in Marion in 1860 to Amos and Louisa (Bouton) Kling, Florence was the oldest of three siblings. She loved dogs and owned a spirited horse named Billy. Florence participated in the popular roller skating craze of the late 1800s and joined her friends ice skating on Marion area ponds.

Amos Kling was one of the business pillars as Marion grew from village to city. His humble beginning in Marion as a clerk in a hardware store gave way to his own business, A.H. Kling & Bros. hardware store. A smart businessman, he purchased and leased large tracts of farm land, participated in a business importing French horses, started several banks, and invested in many of Marion’s early businesses. By 1870, when Florence was 10, he was Marion’s richest man.

Kling’s new social stature—and growing fortune—allowed Florence to enroll in Miss Nourse’s School, which became the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music, after completing the local schools. In Cincinnati, she was trained as a classical pianist and honed her love of opera and classical music. The rare Cycloid piano that she played in her parents’ Marion home resides at the Stengel-True Museum and will be featured at the new Warren G. Harding Presidential Center.

At 19, Florence shocked Marion—not to mention her parents—by eloping with Henry A. DeWolfe on Jan. 22, 1880. Their son, Marshall Eugene, was born in late September. The marriage ended in divorce in 1886, although Florence and Henry already had led separate lives for several years. She reclaimed her maiden name and moved forward from what she knew had been a tragic mistake.

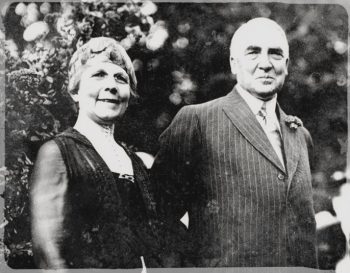

Two years later, Florence and Warren G. Harding met at a local dance. Harding was the handsome young editor of The Marion Daily Star and five years her junior. The pair married in their newly built home on Mt. Vernon Avenue on July 8, 1891.

Two years later, Florence and Warren G. Harding met at a local dance. Harding was the handsome young editor of The Marion Daily Star and five years her junior. The pair married in their newly built home on Mt. Vernon Avenue on July 8, 1891.

Florence had a keen mind for business, thanks to her father. She eagerly adopted The Star as the family business. Florence refined the paper’s home delivery operation by having The Star directly hire newsboys. She taught the boys what we would now call soft skills–how to converse with their customers in a polite manner, the importance of delivering their newspapers on time, and how to act as responsible representatives of The Star.

With The Star on solid financial ground, Warren Harding turned his attention to public service. Florence always believed strongly in her husband’s potential and was comfortable in the male-dominated world of politics. As Harding worked his way through elected positions of state senator, lieutenant governor, a failed gubernatorial bid, and then a U.S. Senate seat, Florence was Harding’s dependable sounding board. The Republicans urged Harding to run for president in 1920—and Florence was adamantly against the idea. By the time Harding threw his hat into the ring, though, Florence was on board 100 percent.

During Harding’s front porch campaign in 1920, which drew more than 600,000 people to Marion during just three months, Florence was a tireless worker. Despite recurring bouts of chronic kidney disease, she gave interviews, talked to visitors on the porch, stuffed envelopes and acted as Marion’s hostess for what she called “the greatest epoch of my life.”

Harding’s election to the presidency naturally elevated Florence to the role of First Lady. Although never a suffragette, Florence gave women a forum through her national position. She invited the approximate 40 Washington-area female journalists to the White House for “chats,” arranged for women scientists, such as Madame Marie Curie, to come to the White House, and promoted appearances by female athletes, musicians, and singers at what she called “the people’s house.” She urged women to get involved in the political process – no matter which party – and make their voices heard. Above all, she listened to women from all social and economic standings, often inviting divorcees and single working women to the White House for tea and answering letters from women across the country.

Florence’s call to help the disabled veterans from World War I was dear to her heart. Her frequent visits to the hospital wards and events at the White House designed for wounded vets complemented her husband’s accomplishment of starting the Veterans Bureau. Mrs. Harding also gave her time, energy and money to groups fighting against cruelty to animals.

Florence’s call to help the disabled veterans from World War I was dear to her heart. Her frequent visits to the hospital wards and events at the White House designed for wounded vets complemented her husband’s accomplishment of starting the Veterans Bureau. Mrs. Harding also gave her time, energy and money to groups fighting against cruelty to animals.

President Harding was in office just 29 months. He died in San Francisco after suffering from congestive heart failure and then, a fatal heart attack. Florence was a stalwart leader for the nation during that shocking, sad time. After her husband’s death, Florence took rooms at the Willard Hotel, but soon returned to Marion as her health failed. She resided in the Rose Cottage on the grounds of the Sawyer Sanitarium on White Oaks Road, then in the home of Dr. Charles and Mandy Sawyer for both the medical care and the close friendship. She died just 15 months after her husband, on November 21, 1924, at the age of 64. She and President Harding are buried in the stately Harding Memorial Presidential Gravesite.

#MarionMade #WeAreLeaders